Sand Hill Road is Now the Wall Street of the West Coast

Everyone is talking about replicating and building the “next Silicon Valley” with the rise of Silicon “roundabouts” and Silicon “beaches” in several locations around the world. While this is going on very few people are talking about how Silicon Valley is evolving: specifically that Sand Hill Road is now the Wall Street of the West Coast.

The rise of the “Uber” Round

More and more tech startups are raising hundreds of millions or even billions of dollars in later stage “uber” rounds. (I call these the “uber” rounds as a play on the German for “super” or after the company Uber that has raised well over $4 billion in Venture Capital.) As of this writing, Lyft has just closed a $680 Series E. According to Crunchbase, Lyft is one of 20 startups that have raised $1B or more in venture funding in the past 5 years.

Companies are going public later and later, a trend started by Facebook; instead of rushing to an IPO, companies are staying private longer and are taking more and more uber rounds. (Some people think that these companies should be going public as the investing public can’t participate in the later stage growth, allowing the rich to get richer.) The average amount of money that companies have raised before going public has been going up, more than double since the 2008 downturn.

What is Going On?

Most pundits think that companies are staying private longer to avoid the hassle and expense of going public as well as regulations like Sarbanes-Oxley. While those are all reasons to stay private, the real reason is that Silicon Valley VCs on Sand Hill Road have evolved to grow larger and focus on late stage massive growth.

Typically an IPO is for massive growth. A company will get to a certain stage of maturity and then raise anywhere from $300m to over a $100b at an IPO. The IPO accomplishes a few things: allows early investors and employees to “cash out” and sell their shares to the public as well as provide much needed capital for massive growth.

Today companies are delaying the IPO and raising the growth capital with their uber rounds. On the surface this looks crazy. But in reality, it is genius.

Lean Startup and Uber Rounds

Let’s take a made up startup LeanCo as an example. Assume LeanCo already took a Series A ($8m) and Series B ($30m). Now they are kicking butt and are growing at the same rate as the other high performing startups. Say they have well over $250m in sales, expanding market share, healthy margins, and are expanding internationally. This is the textbook case for an IPO.

What would happen is that LeanCo would go to a big Wall Street bank and raise approximately $5-$10+ billion in an IPO. After all the costs and fees and the Wall Street bank’s cut, the company would have a lump sum of money, let’s just say $5b. Now the company has the war chest it needs in order to grow. Typically LeanCo will acquire smaller rivals, enter new markets, and build out new products and services.

Instead, the LeanCos are choosing to raise billions for growth before an IPO. Instead of raising $5b in an early IPO, they are raising $2-5b privately before a much later IPO (at a much higher valuation.) They are raising the money $400 or more at a time. Here lies the genius of this approach: LeanCo only raises what it needs, when it needs it in a private (closed) market that will provide a higher valuation than a public one. There are also other benefits to staying private during the growth stage, like not disclosing your financial health and spending to competitors.

For the investors, this is actually a much more conservative approach. By only giving LeanCo the money when it is needed and doing it incrementally, LeanCo has to operate in iterative cycles similar to the Lean Startup and Agile Development. For example, if investors provided LeanCo with $5b in one lump sum, LeanCo may spend it unwisely feeling that they have a lot of capital on hand. If investors give LeanCo $400m or so at a time, LeanCo will have to take an incremental approach. If LeanCo were to go under after an IPO, investors would lose all of the $5b. If LeanCo were to fail after raising “only” $2b, investors lose far less money.

The Post-IPO World

The VCs on Sand Hill Road in Menlo Park have changed the game. I remember in the .com bubble, the largest Venture Fund was $1b and the largest deal was around $75m. Now the VC funds on Sand Hill Road are all well over a few billon each and think nothing of leading a $500m round.

Eventually the startup companies are going public, however, that is only because at some point they have to in order for the VC investors to sell their positions and the employees to cash in their stock options. I’m sure that over time, Sand Hill Road will evolve past the IPO, where companies stay private forever and large East Coast financial institutions buy back those positions from the VCs and earn returns via dividends, etc. You are already starting to see the signs of this when large pension and investment banks such as Fidelity, T. Rowe Price, and Goldman Sachs are part of the last round of financing for companies like Lyft, Box, and Uber. In the future, you won’t be able to buy shares in a Facebook individually, but you will buy shares in a Fidelity “Silicon Valley” Mutual Fund. Silicon Valley is disrupting Wall Street.

What Does this Mean for Startups in Silicon Valley

We all know that New York City and Wall Street is the IPO center of the world. Did a startup have a competitive advantage by being located in New York? As a native New Yorker who built three startups in New York City, I can confidently say no. Mark Zuckerberg proved that when he showed up to his Wall Street pre-IPO meetings in his hoodie. When your company is ready and has the right numbers, the Wall Street Investment Banks will work with you, no matter where you are.

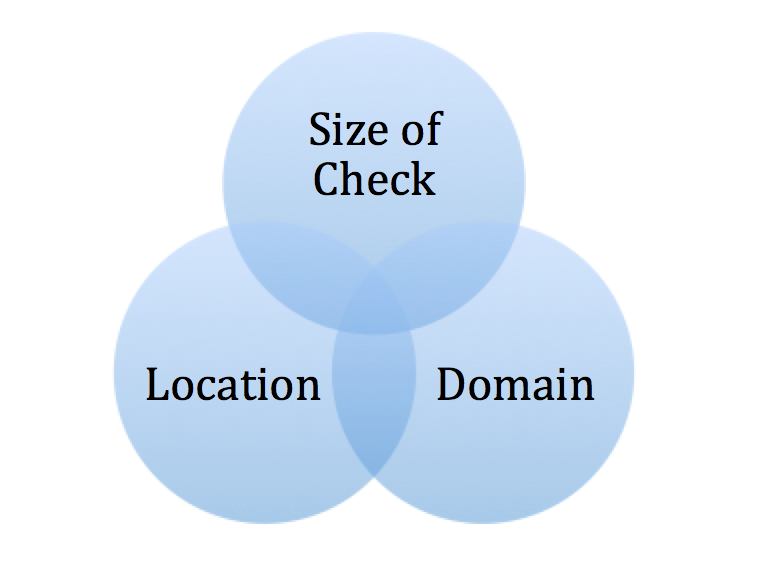

What about tech startups located in Menlo Park, Palo Alto, or Mountain View, close to Sand Hill Road? (Sticking to the geographical description of Silicon Valley.) Same thing, when your company is large enough to take the uber rounds, it does’t matter if you live in Menlo Park or Montana, or Mongolia, the VCs on Sand Hill Road in Menlo Park will work with you. You are already seeing this with startups being located in the City of San Francisco and not down south in Silicon Valley. The larger established companies such as Facebook (Menlo Park), Tesla (Palo Alto), Google (Mountain View), etc are down in Silicon Valley, but the young, early stage startups are up in San Francisco. This means San Fransisco is about the startups and Silicon Valley is about the money.

San Francisco is the new Silicon Valley. Silicon Valley is the new Wall Street.