How to Successfully Raise a Series A

It’s no secret, the widespread idea is that there’s a Series A gap in startup funding. You can easily raise a $1 million seed round and $100 million Series D, but somewhere in the middle things get a little dicey.

But as I’ve said before, there’s really no such thing as a Series A gap. Some companies just try to swing for the fences a little too soon and don’t drum up a lot of interest. Rather, they don’t focus intently on what they need to prove to secure the Series A or they focus on things that they think investors want to see.

The key to understanding the supposed gap, is that if your startup is really ready for a Series A, you can most assuredly raise money. You just need to be able to prove that your company has a repeatable and validated business model that can be scaled before walking into those meetings.

And this doesn’t mean you need to have tons of customers and millions in revenue by any means — a common misconception in today’s startup world. To raise a successful Series A round, start by proving the pipeline — and making financial projections based on it.

The Difference Between Seed and Series A

Seed money is supposed to help your startup figure out its business model. Seed is where you tell the story of what you are going to do. Series A, on the other hand, is more about making sure your business model works. You’ll also want to execute your story, telling people what you’ve done and what you’ll do next.

Let’s say you want to sell new coffee cups. During your seed, you should first focus on landing one or two landmark customers; maybe a few Starbucks locations that are proving to be loyal and consistently fill orders. When you’re pitching the Series A, show the investors that you can scale your business to every other Starbucks in the Palo Alto region and beyond, as well as Peets and other coffee shops — and the investor’s money is what stands between you and accomplishing that growth.

The Wrong Approach to Series A

Today, because of the emphasis on hitting a revenue target to signal a new round of funding, a lot of startups are guilty of growing their revenue linearly.

Imagine Starbucks is buying your new cups and you’re generating $50,000 ARR from that account. Then you decide to do non-core business model activities that pad your overall revenue. Maybe you consult for Peet’s Coffee and help out other startups in exchange for quick cash to keep the runway looking a little better.

Sure, all those extra funds are lumped into your total revenue. But let’s face it, that’s not the organic, scalable growth VCs are looking for.

You’d be much better off getting that one customer that fits your model, making some revenue off that sale, and then trying to get one more customer to show the pipeline potential. Focus on your core business, and a Series A will become that much easier.

Startups Love Revenue

It’s no secret that startups will chase revenue wherever it’s coming from. When you’re chasing a Series A, you’ll try to make whatever money you can to prove you have a business that generates revenue.

But let’s face it, not all revenue is created equal. This doesn’t mean revenue is necessarily bad, but time spent chasing after any revenue in sight can be a dangerous game in the early days of a startup.

There’s a common misunderstanding in the VC/startup world that a $1 million run rate means you’re ready for a Series A. In reality, there isn’t a benchmark that indicates the exact time you’re supposed to start raising money. Your run rate doesn’t matter as long as you can talk to investors about projected metrics.

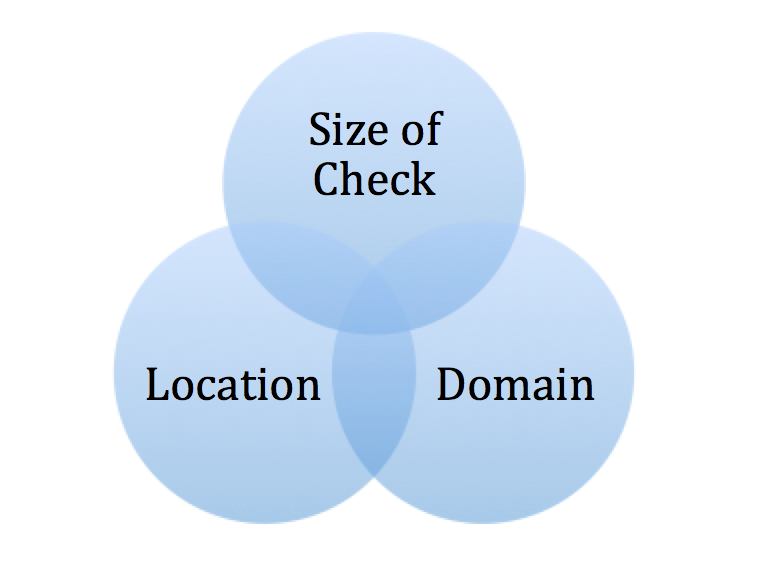

How does that work? Start with your pipeline and your pipeline’s future. Show repeatability and show scalability. Show investors your funnel and the pipeline that goes into that funnel and tell them how you’re going to get there. That way, when you ask for lots of money to hire a certain number of salespeople and marketing folks, your request will be validated by the data up on the screen.

Whether you’re in a SaaS, B2B, or B2C business model, the same rules will still apply. So if it’s projecting growth in sales, the viral coefficient, or whatever else to show future scale, investors need to see the pipeline view of that story as validation before taking part in the round.

Key Takeaway

If you’re still trying to tell your company’s story, rather than actually using sales data to project growth, you’re likely better off waiting and raising a seed extension round.

How do you do that exactly? First, go back and see if your original investors are willing to go further in with you to bridge the company through to the next round; this may require you to give up more equity, but it will also be crucial to keeping the proverbial lights on. Also take time to look for firms that aren’t necessarily specializing in “Series A and above” funding — there is an abundance of seed stage investors out there looking to fill that gap.

Once you have an idea of how your business model will become scalable, use the extra time and cash to refine that story, validate the numbers, and make it real before pitching to Series A investors. This allows teams to focus less on generating non-core business model revenue, and more on securing a few necessary customers to project a data-backed pipeline. Once that happens, and you’re getting great feedback that shows the product or service is truly valued, it’ll finally be time to show later stage firms a clear vision of what you plan to do next.