Avoid Premature Scaling at Your Startup

I recently recommended a friend for a PM job at a hot Silicon Valley startup run by another friend. The startup recently raised a big Series A and was looking to scale. I know the risk of linking up two friends in an employment scenario, however, my friend was more than qualified for this job and my founder friend really needed the position filled.

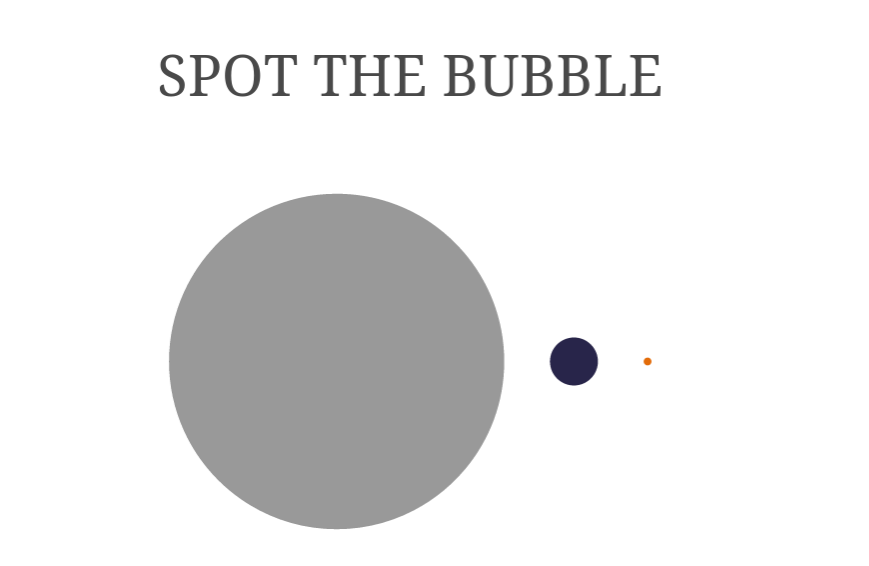

While my friend was more than qualified, interviewed well, and the team loved him, etc, the founder decided to pass on my friend. The reason: another candidate with the same skills and experience came along that they hired. The difference between the hired candidate and my friend? The candidate that was hired had the same PM experience but all at big companies like Facebook, Amazon, and Google. My friend has spend his entire career at startups.

My question is: was this the right move? If you had the choice between nearly two identical candidates and one had all their experience at big successful companies and one had their experience at successful startups, isn’t it safe to choose the candidate that worked at the bigger companies?

Put yourself in the founder’s shoes. You just raised a big Series A. You are being pressured by your investors to “go big or go home.” You have aspirations to be a big company. This is Silicon Valley, shouldn’t you hire the absolute best talent we can find? Shouldn’t you hire people who worked at Facebook and Amazon since you want your company to be big like them one day?

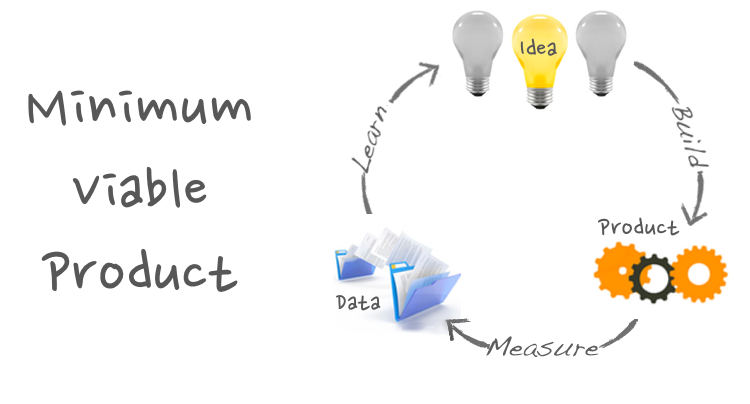

PMs that only worked at companies such as Facebook and Amazon are super qualified PMs. Huge plus. They also know next to nothing about building a startup. Huge negative. People from larger companies bring the bigger company process, procedure, and culture with them. This leads to premature scaling of your business. The problem is that your startup is not a smaller version of a bigger company. As Steve Blank says, a startup is an experiment looking for a business model, not a smaller version of a larger company. Facebook as over 10,000 employees and billions in profits. My friend’s company has less than 15 employees and no profits. Hire people comfortable working in that environment, who know how to bring a company from 15 people to 150 people. When your startup has 1000 employees and is super profitable you should start to hire PMs from Facebook. In between, you have to hire people who can not only do the job, but also help you grow the business, shape the culture, and constantly evolve the process.

I made this mistake several times at my past startups. At one startup we realized that we needed an HR manager. Since we had plans to “go big” we wanted to hire an HR manager who came from a big company. Big mistake. We were a team of 12 but all of a sudden we were doing 360 reviews and had to fill out a form in order to take a day off. At another startup we wanted to enter the “enterprise” space, so we hired some “enterprise” software people from a large enterprise software company and gave them fancy titles. The problem is that people who work as executives at big companies usually don’t roll up their sleeves and build a product. Nor do they know how to scale a company, they know how to keep a big company big, but don’t know how to build a big company. In addition they wanted to fly business class and have personal assistants, things that did not jive with our startup culture.

Avoid premature scaling at your company and hire not only the candidates with the best skill set, but also with experience in working at and building a startup. Later on when you are bigger and more mature should you hire the people with bigger company experience.