The Most Effective Way Governments Should Support Startup Ecosystems

I once met an active angel investor from Europe who was convinced that government subsidies of investors were the most effective way to build startup ecosystems. Of course I asked the obvious question, “what about Silicon Valley?”

“Except Silicon Valley” was his reply.

Huh. Lightbulbs going on everywhere (at least in my mind).

The Best Intentions

Small scale grants to get startups off the ground in place of friends, family and fools money certainly makes sense. After all, most people actually don’t have friends, family and fools with enough money to support them.

What about when governments start subsidising rich angel investors with tax breaks? While this may be the result of genuine intentions to encourage risk taking, if investors are ultimately viewing startup investments as tax deductions, then this is a fundamentally flawed strategy. Instead of being investments, startups are transformed into tax loopholes.

Moving up the investment value chain, it’s certainly admirable for governments to actively support local venture capital because there is a positive knock-on effect of helping the real economy. This leads to a natural question:

How should governments support local venture capital funds in order to scale and build a local ecosystem?

One approach to building a local venture capital ecosystem is to provide rebates and other complex incentives where the government takes on more risk and leaves the private sector with extra return benefits. No matter what the fancy official name of this kind of program, it is effectively a subsidy.

As a venture capital investor, I’m supposed to jump at the chance of getting subsidised returns. Call me old fashioned, but I don’t want to receive subsidies to juice returns because it’s wrong for society (my altruistic side) and I don’t want my returns to be artificially boosted by subsidies (pure ego).

Fortunately, there’s a simpler idea.

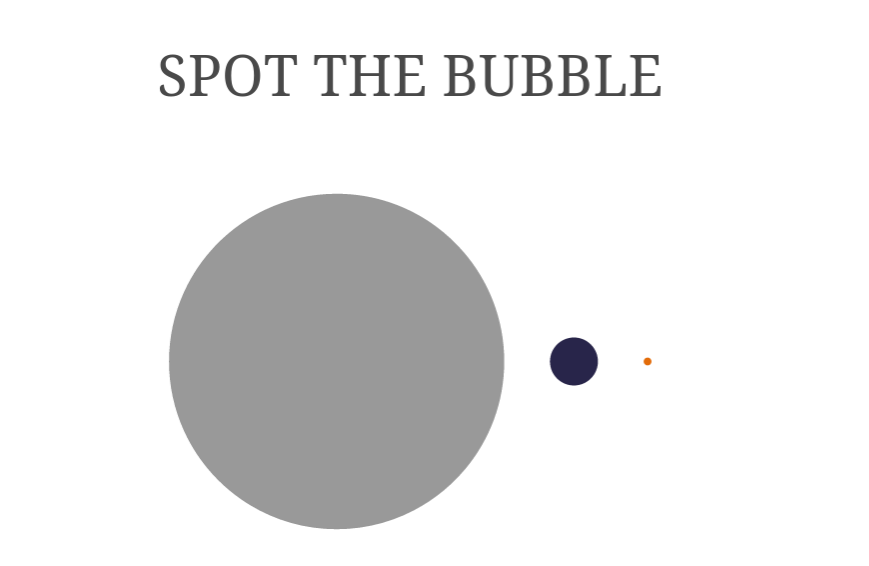

Instead of tilting the risk / return in favour of funds via subsidies, government related capital should simply be open to investing in new venture capital funds on market terms. The boring reality is that most government capital is allocated through various intermediaries and by the time it gets to venture capital funds, many decision makers take the view of something like this:

New venture capital funds are too risky, so we prefer teams that have worked together for at least 10 years and are raising fund 5.

If you want to attract venture capital investors to your local ecosystem, it’s a lot easier to do so before fund 5. Rather than throwing around subsidies to attract funds, governments should take a hard look at how their existing capital is being allocated through various intermediaries to make sure that there is an allocation for emerging venture capital funds.

If done correctly, this market driven approach will actually increase returns, as there’s plenty of data to show that new funds are generating outsized returns. Instead of spending money to subsidize venture capital funds, governments can get more money through higher returns.

The Unintended Consequences

Beyond the obvious concern that governments should not be subsidising investors directly, there is also the problem of unintended consequences.

At the company level, since small scale grants for startups to get off the ground usually do make a positive impact, it’s very tempting for governments to scale that up.

Unfortunately, when companies raise institutional capital which was only possible because of subsidies tied to the investment either directly or indirectly, the incentive mechanisms tend to train grantpreneurs.

The reality is that all startup subsidies come attached with complicated forms because governments need to protect themselves from criticism. So there is no such thing as “simple startup subsidies”.

Grantpreneurs are extremely efficient and skilled at filling out the complicated forms and ticking all the right boxes for subsidies but unfortunately are a lot less skilled in building successful businesses.

People improve their skill through repetition. The worst case scenario is creating serial grantpreneurs, who are able to jump from subsidy to subsidy.

One of the goals usually cited by governments to subsidise investors is that this will then lead to more jobs. Of course, there are usually many restrictions on the people who may be hired.

This prescriptive approach to hiring can actually lead to increased inequality because it increases demand for a fixed pool of talent rather than increasing the overall pool of talent. Wages go up for those already with skills. Everyone else, not so much.

Throwing money at jobs is not the same as increasing the overall pool of talent.

A Better Way

Should we just throw our hands up in the air with the view that governments are always wrong and it’s foolish to mess with markets?

Not quite.

Markets are far from perfect and as the impact of technology continues to accelerate, cities and countries that do nothing to build thriving startup ecosystems are at risk of being left behind.

So what should governments focus on when it comes to extra support for startup ecosystems?

Ultimately, every government has limited resources and a key starting question should be “what is the best use of our resources for maximum impact?”

If the goal is to encourage innovation across society and the improvement of overall welfare, better to focus on talent.

What would a program to support talent look like? Rather than giving money to startups, which would empower grantpreneurs to fill out forms more successfully, governments should be subsidising individuals to learn new job skills. To be clear, this does not mean training everyone to become an entrepreneur.

Empowering individuals to make their own job skill education choices at least creates a pathway for them to find new job opportunities. It won’t work for everyone but it has the potential to enhance the overall pool of talent at scale. So rather than funnelling more money to the same number of people, there will be a broader base of talent.

Will there be inefficiency? Of course yes.

Will there be fraud? Probably.

But at least by focusing on individuals, the magnitude of any individual fraud case should be smaller.

Even with inefficiency and fraud, as long as the overall talent pool is improved, then this approach could create massive value for society.

The Unexpected Benefits

Beyond the direct impact of enhancing the talent pool, there is an important secondary benefit: increasing the quality of overall talent should attract more institutional capital.

Why does increasing the pool of talent attract more capital? Because capital follows talent.

Just take a look at the history of Silicon Valley. The talent moved first, led by pioneers like the Traitorous Eight, and the capital followed.

There are two factors behind this dynamic. First, great talent is still scarcer than capital. Second, it’s easier to move capital than talent.

So by focusing on improving the talent base, governments will naturally be building the foundations of attracting capital for the right reasons.

The First Steps

It’s tempting for governments to go big with a fancy launch party and lots of hype around a new program.

But for a talent subsidy program to actually be effective, better to act like a startup and start with a small test. Make it small because then the mistakes will be small and there is only one guarantee with a talent subsidy program: there will be mistakes.

Then this is the most important part: get feedback, learn from the mistakes, and don’t scale up until it’s actually working on a small scale.

This means less publicity in the short-term but ultimately much larger positive impact in the long-term. It’s a marshmallow test for governments who want to support startup ecosystems.

Lightbulbs are a metaphor for new ideas and innovation. If governments truly want to support startup ecosystems, they should be focused on helping people find their unique lightbulb moments.

For anyone else interested in figuring out how governments can help support startup ecosystem talent, please get in touch.